WoT's Hot

After more than a dozen visits to South Africa, made glorious with its wildlife adventures at Kruger, the scenic drives along the Garden Route, the tantalizing seafood and the tastings at the Stellenbosch wineries of Cape Town, just chilling on the golden beaches at the seafront promenade of Durban, gawking at the splendid Sun City where we were there for its opening and the first Miss World contest and trawling the tribal flea markets, among many other forays, it was time to get back into some historic reflections.

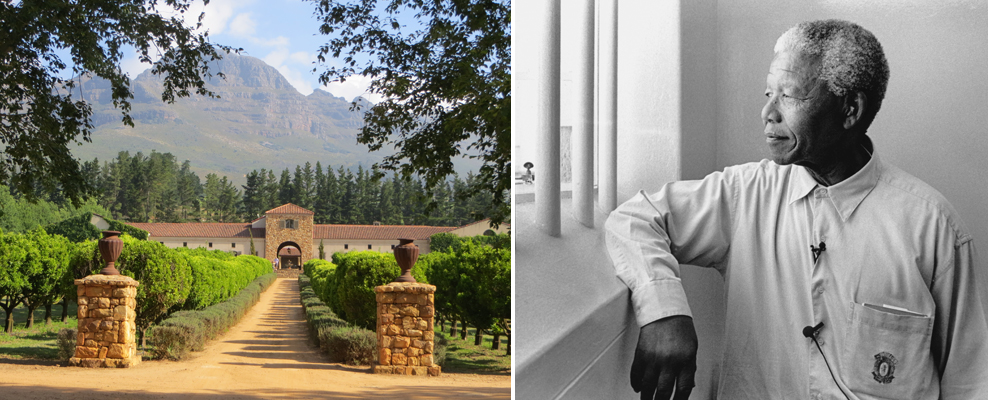

But before I take you through the tour of Constitution Hill, our history connect, and the Gandhi-Mandela story, one cannot but mention our all-pervasive cricketing adventures. 1991—the year after Dr. Nelson Mandela became a free man from his Robben Island incarceration and the UCBSA (the United Cricket Board of South Africa) hosted a banquet where the likes of Sunny Gavaskar and my husband were invited. The next year, one was to meet the great man himself – Dr. Mandela, at the Wanderer’s Cricket Stadium, when India played South Africa for the first time after apartheid was lifted. Wanderers stadium was a place we were to frequent in subsequent years, along with the other stadia − the Centurion, Newlands, and even the small, picturesque Paarl in the Western Cape Province.

The World Cup in 2003 brought us heart stopping excitement as India trounced Pakistan and we launched Portraits of the Game, a coffee-table tome featuring 60 of the world’s best one-day cricketers, at a champagne brunch in Pretoria. 2009 took us back to South Africa, what with the IPL shifting base to that country, as we took in some great matches from the luxury of hospitality boxes.

Constitution Hill

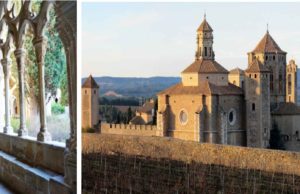

But this time, as winter was somewhat on the wane, with crisp, cold evenings and sunshine- filled days, we decided it was time to revisit history. Constitution Hill is actually the Seat of the Constitutional Court of South Africa. It is a unique must do when you visit Johannesburg, for it is a living museum which, no holds barred, gives one the whole story of South Africa’s journey to democracy. You must take a guide − and ours was a local young woman, extremely well-versed in her facts and lucid to boot. She led us through the various buildings at the site, which is a former prison and the site of a military fort that bears the scars of the country’s tumultuous past. The day we were there, the court was in session.

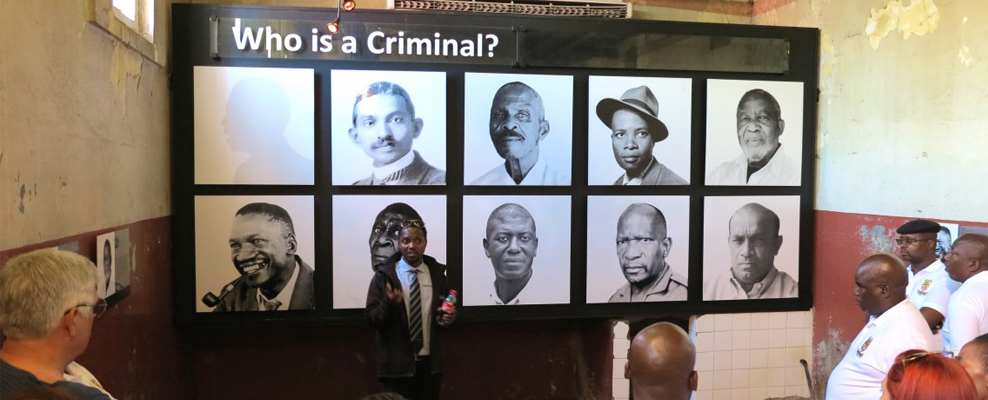

We were told that there is “perhaps no other site of incarceration in South Africa that imprisoned the sheer number of world-renowned men and women as those held within the walls of the Old Fort, the Women's Jail and Number Four. Nelson Mandela. Mahatma Gandhi. Joe Slovo. Albertina Sisulu. Winnie Madikizela-Mandela. Fatima Meer. They all served time here. But the precinct also confined tens of thousands of ordinary people during its 100-year history: men and women of all races, creeds, ages and political agendas; the indigenous and the immigrant; the everyman and the elite. In this way, the history of every South African lives here.”

Furthermore, to quote the literature on Constitution Hill, it is “a place of contrasts: of injustice and justice, of oppression and liberation. Our precinct is testament to the importance of preserving sites of atrocity for posterity, and also to recreating them so that they can serve the purposes of the present and serve to mould the future.”

We are led to Number Four, the Old Fort Prison complex. In the original prison, it was white male prisoners who were kept and the Old Fort was built around this prison by Paul Kruger in the late nineteenth century to protect the South African Republic from the threat of British invasion. Later, the prison was extended to have “native” cells, and a women’s section was added too.

On the one hand it served as a detention centre for political dissidents opposed to apartheid. We mentioned some of the names earlier. However, we were to witness the remains of the jail interiors, even the solitary confinement blocks, where the most inhuman treatment was meted out to prisoners, gory details not even worth repeating on these pages.

But to the credit of the authorities, people can witness the devastated and the new, particularly the Constitutional Court, which was newly built using bricks from the demolished awaiting-trial wing of the former Number 4 prison. The first court session in the new building at this location was held in 2004. It is open to the public who can attend hearings or view the art gallery in the court atrium.

As we came out of the court building, in the middle of a plaza and built into one of the stairwells of the old prison, we found a perpetually burning Flame of Democracy, pictured here. The Flame was lit in 2012 when South Africa celebrated the 15th anniversary of the signing of the constitution.

Also pictured here is the bust of Mahatma Gandhi, and a meticulously put together exhibition on the premises of Gandhi and Mandela. The core of this exhibition is to present the similarities between the two leaders, trace their plot and plot the trajectory. When Nelson Mandela was awarded the Nobel peace prize in 1994, he claimed that he owed his success to Mahatma Gandhi. He said: “India is the Mahatma’s country of birth; South Africa his country of adoption.” Much of the synergy comes through. He was inspired by Gandhiji’s satyagraha philosophy and he visited India many times. In one of the panels, Mandela’s quote with his picture goes like this: “Gandhi taught himself Tamil in prison. I taught myself Afrikaans. Gandhi writes that one of the most important benefits he derives from being in prison was that he got the opportunity to read books. He read in English and Gujarati. Books were also my refuge, when I was allowed them.” A lot of artefacts preserved there are items we might not find in India—both display and choice have been exemplary.

After more than a dozen visits to South Africa, made glorious with its wildlife adventures at Kruger, the scenic drives along the Garden Route, the tantalizing seafood and the tastings at the Stellenbosch wineries of Cape Town, just chilling on the golden beaches at the seafront promenade of Durban, gawking at the sp

What to read next

Featured articles

Welcome Festive Season in Glam, Latin Quarters Launches new #PujoBling Collection with Monami Ghosh

by WOT