WoT's Hot

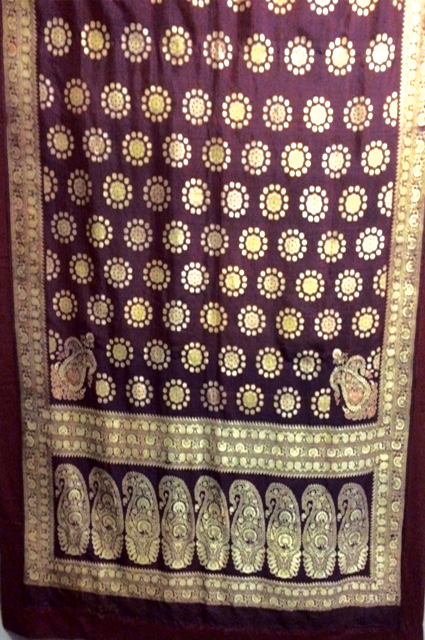

We often talk glibly about revival, as if it were a patch of darning that could keep a frayed garment from falling apart. But when a whole culture, a weave of life, a living, talking fabric, the Baluchari saree has been given an enhanced set of ways to find its rightful status, that is when there appears to be hope that it will survive. And grow.

When Darshan Shah, Founder-Director of the Weavers Studio Resource Centre (as well as the Weavers Studio Centre for the Arts) brained the macro concept, it embraced the whole monty. There was a grand exhibition of Balucharis culled from khandani homes and collectors which was curated by eminent designers. Followed by a deep day-long seminar with experts helming it and a knowledgeable set of participants to boot, beautifully illustrated and deeply researched book with important scholarly inputs, artisans at hand with live looms, journeys to Bishnupur for those interested to see and imbibe where the saree is spun amidst its myriad terracotta temples, buyer-seller meets—everything set to take on the reinstating of this art form.

It turned out to be a festival of mega proportions. The Birla Academy of Art and Culture was the venue, for “Baluchari—Bengal and Beyond”, its halls resplendent with displayed sarees that meticulously gave the history of each piece, displayed from the Tapi collection of Surat, from the Weavers Studio Resource Centre and from many private collections. And for the benefit of today’s fashionistas, come outfits by major designers to show how the Baluchari could be recreated into a garment of fashion.

Real artisans were present as were women gloriously attired in their choice Balucharis, including those inaugurating on different days like eminent Director Aparna Sen and the glamorous MP from Bankura, Moon Moon Sen and other important government functionaries. The lawns too held other surprises—display and sale of handicrafts, and music interludes and puppetry to enhance the concepts of Baluchari—nothing that could not fire a person’s imagination.

The seminar was a major highlight. When top experts, historians and textile specialists converge at one such tightly loomed program, the outcome has to be something that is a positive preen, a jumping off point for people to take the idea, the movement, the revival, the restitution, several steps ahead. To not lose the threads, to push for better conditions, more fine-tuned utilization of technology to give weavers an impetus, to contemporize, without losing context and tradition.

What a line-up of speakers. Jyotindra Jain, Co-Editor of Marg Publications and a Member of the Internatioanl Advisory of the Humboldt Forum—a major multi-arts project in Berlin. Tulsi Vatsal, Oxford graduate who has authored several key publications on Indian history. Ruby Pal Chowdhury, one of India’s leading voices and activists in the field of craft and Honorary General Secretary of the Crafts Council of West Bengal. From Kolkata, too, Kasturi Gupta Menon, former IAS officer who has worked tirelessly for many decades in the revival and development of craft in India. B.B. Paul, consultant in the office of the Development Commissioner for Handlooms and Inventor of four looms aimed at increasing efficiency of production in Handlooms, to reduce fatigue to weavers. Jasleen Dhamija, internationally renowned in the field of textiles and costumes, greatly known for her pioneering work in researching and developing the handicraft and handloom industry, fork and performing arts and women’s employment. Naseem Ahmed, a weaver, master artisan and Naqshaband based in Benaras, and great grandson of master artisan Ali Hasan, better known as Kallu Hafiz—instrumental in the Baluchari revival in Benaras. Monisha Ahmed, famous for her articles and books on textile arts, particularly those centered around the art practices and material culture in Ladakh. Ritu Sethi, Chairperson of the Craft Revival Trust and Editor of the principal online encyclopaedia on the arts, crafts, textiles and its practitioners in South Asia. Mayank Mansingh Kaul, Delhi-based textile designer working with contemporary craft. And Rosemary Crill, who carried the thread of the discussions seamlessly, a known face in Kolkata, who has recently retired as Senior Curator for South Asia at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and who has published widely on Indian textiles and paintings.

The seminar took us through the Cononial Art forms of the 19th and 20th Century Bengal: Situating the Baluchar in that era; a presentation on the Elegance and Enigma of Baluchar, a panel discussion on Baluchari in Bengal; the focus then shifting to the Baluchari in Benaras, and going on to the Shifting Perspectives—negotiating the Contemporary in the traditional.

The seminar took us through the Cononial Art forms of the 19th and 20th Century Bengal: Situating the Baluchar in that era; a presentation on the Elegance and Enigma of Baluchar, a panel discussion on Baluchari in Bengal; the focus then shifting to the Baluchari in Benaras, and going on to the Shifting Perspectives—negotiating the Contemporary in the traditional.

Counterposing viewpoints embracing aesthetics, history, techniques, trade and cultural anthropology. And plenty of discussion on the patterning—the royal motifs that endured, the everyday scenes that crept in, the passionate and elaborate pallas, the colors, images that harked back to master weaver Dubraj Das of another era.

It’s not just discussion and debate on these and other aspects like GI, but much, much, more that appears to be on the cards, what with the efforts from Tantuja, the West Bengal State Government’s Weavers’ Cooperative Society and Weavers Studio Resource Centre, an NGO under Darshan Shah that is working towards reviving Bengal’s lost traditions with increased looms and more jobs to be created. The tradition is surely here to stay, the technology needs more upgradation, the tenacity needs to be woven into the whole warp and weft of these initiatives.

One particular Baluchari that I am still in search of is something that was woven in the nineteen seventies, not that very long ago, and displayed at an exhibition. No noblemen or howdahs, but the whole story of Job Charnock landing in Sutanuti, done in English hues of blue and pale pink. Where could it be?

We often talk glibly about revival, as if it were a patch of darning that could keep a frayed garment from falling apart. But when a whole culture, a weave of life, a living, talking fabric, the Baluchari saree has been given an enhanced set of ways to find its rightful status, that is when there appears to be hope that

Other Articles in Kolkata & Bengal

What to read next

Featured articles

Welcome Festive Season in Glam, Latin Quarters Launches new #PujoBling Collection with Monami Ghosh

by WOT